Finding Dr Geroe's Voice: Reflections on Biography & Psychoanalysis in Australia

Christine B. Vickers

When we write or make history, we talk about ourselves, now.

(Christine Vickers is a Psychoanalytic Psychotherapist and Historian with a doctorate from La Trobe University in Melbourne. She is writing a biography of Clara Lazar Geroe. She was awarded a Regional Fellowship by the State Library of Victoria in 2019/20.) Ed.

I am on the phone, talking to a woman I have met for the first time. She is the daughter of Dr Maida Hall, trained by the Hungarian Analyst Dr Andrew Peto during his seven-year stint in Australia from 1949 until 1956. In January 1956 Maida Hall had put her daughters into boarding school. She then travelled to London for a year, to present herself to the British Psychoanalytic Society for accreditation. Hall had first met Peto in mid-1952 when she took one of her other daughters for a consultation. He had taken Hall into analysis and subsequently accepted her as a trainee.

‘Oh, my mother was so lively’ the woman said. She was ‘out there’, gregarious, interested in life, the ultimate extravert and, perhaps, self-centred. For her daughter the sense of abandonment when her mother departed was acute. She remembered the long barren, empty months waiting for her mother’s return from London when delight and exasperation could begin all over again.

In Sydney during 1956, there was talk of Hall becoming a training analyst ( Neild to Geroe C. September 1956). She would take over the role from Andrew Peto whose American visa had finally come through early in the year. Since then he had been commuting back and forth, between Sydney and New York, and consulting with his Melbourne colleague Dr Geroe over the future of training in Australia. Questions were being raised from Britain about whether analytical training could proceed if there was not a second analyst available to supervise candidate’s analyses. Dr Geroe, also a Hungarian émigré, had arrived in Melbourne in March 1940. Almost singlehandedly she had established a program of psychoanalytic study groups and training. She had lectured to parents, teachers, psychology and medical students, introducing them to Freud and child development. Her colleague, Andrew Peto’s arrival had been a great relief. Not only was he a friend, colleague, and second fully qualified psychoanalyst in Australia but he was also a solid theoretician and leader. He, in turn, respected her clinical acumen ( Peto 1981). She had her own place in the Hungarian Society. When their mutual friend and colleague Alice Balint had died suddenly in August 1939, six months after her emigration to Britain, Alice’s mother, Vilma Kovacs, had invited Klara to give the eulogy to the Hungarian Society. Klara had got it right, Kovacs had said. She too, had died within the year ( Borgos 2022, p.135).

Maida Hall’s daughter slowly relates her story. Her mother had returned to Australia in October 1956. Clearly suffering from cancer, she was a hollow of herself. Far too ill to practice Hall declined over the next year. ‘I ran away’, Hall’s daughter said. ‘I couldn’t bear it’. She was only fourteen years old (CV and Ms X phone call 27 March 2019).

Maida Hall died from intestinal cancer at Rose Bay in Sydney on 28 October 1957. She did not practice after her return to Australia. (CV and Ms X, 27 March 2019).

In his account of Australian psychoanalytic history recorded in Kutter (Martin in Kutter 1995, pp. 27-39), Professor Reg Martin describes Hall’s inspiration for him. She was his first psychoanalyst. While waiting for his session he discovered Melanie Klein and object relations from books Hall had stored in her waiting room. For him Klein was an eye opener. Her fine analysis of the processes of mind: unconscious phantasy and internal reality spoke to him. Klein’s dynamism and precision, followed by Bion’s theories of thinking are part of the Australian psychoanalytic lexicon. Hall was ‘the first to practice Kleinian-orientated psychoanalysis in Australia,’ he says. Martin states that Hall died in 1962. (Martin in Kutter, 1995 p. 31).

Such errors – dates, times, place - are a regular occurrence in the making of history. People may rely on their own memories or those of others. Yet memory is a notoriously unreliable source. Bion reminds us of the ineffability of truth and how one’s internal constraints and restraints colour understanding and interpretation. It is likely Martin’s mistake is genuine although one wonders whether he checked. The date of someone’s death is public information after thirty years. In the light of Martin’s subsequent discussion of the Australian psychoanalytic history and his criticism of the Hungarian émigré psychoanalyst, Clara Geroe, his error may reflect the high value he placed upon Kleinian thought.

Word limits for historical articles pieces can cause problems. Martin has condensed the events of a twentyfive year time period, first describing Geroe’s early plight as the sole training analyst, ‘responsible for the development of training to the standard of Associate Member’. Then he continues. ‘One of the arrangements made by those (notably Ernest Jones) encouraging Dr Geroe’s migration, was that she was made a Training Analyst of the British Society…Melbourne was to function as a Branch of the British Society, this arrangement was made so that whoever trained in Australia would, under certain conditions, become an Associate Member of that Society. This arrangement was agreed to by the British Society’.

This endured until 1965, Martin claims, when it was challenged by the IPA (Martin, ibid. p. 29). Furthermore until 1968, Martin continues, ‘the one Australian analyst Dr C.Geroe

was responsible for the selection, analysis, teaching, supervision, assessment and finally recommending them for election to Associate Membership, a situation ‘unacceptable today – in 1995 – in any component Society’ ( pp.29-30).

Martin’s statements do not tally with archival sources. He overlooks Frank Graham’s and Harry Southwood’s confirmed status as Training Analysts of the British Psychoanalytical Society by 1960. Geroe herself says that she and her family were ‘twice refused’ a visa (Geroe 1982), before the prospect of a psychoanalytic institute was mooted. As ‘picky’ as these corrections sound, they add up to a narrative in which Martin’s critical attitude towards Geroe is apparent. Whiggishly, for Martin’s account stresses a developmental process towards improvement, judging the past in the light of the present, reminding his readers that analytic training fifty years ago was far less sophisticated than it is today and that coming from Hungary, where ‘the tradition of personal analysis also being the supervisor was standard practice, meant that this mixture of roles was not as alien to Geroe’s way of working as it would be to contemporary analysts’ (Martin in Kutter, 1995, p.30). I have been troubled by Martin’s account, particularly concerning the death of Maida Hall. The errors are common enough. They also suggest that more research is needed. Nevertheless his errors raise some ethical issues about the research and writing of history.

Now to a second, more recent, scenario. I stress here that the errors I am about to discuss were most likely made in good faith and drawing on earlier research. Nevertheless, they illustrate the need for care in compiling even a short history which could, in time, become an authoritative source. It is a tricky field. Yet history, describing the formations of the present, help us to understand ourselves and possibly the future. In January 2024 I received an email from Clara Geroe’s granddaughter. Her younger daughter had found an online ‘Wikipedia’ entry about her great grandmother, Clara Lazar Geroe. The author inferred Geroe was significantly underqualified for her position as a psychoanalyst training other prospective analysts in Melbourne. There is no reference for this. Judith Brett’s short entry on Geroe’s life and career compiled for the online Australian Dictionary of Biography is listed. Brett clearly states that Geroe qualified as an analyst in 1931, nine years before she arrived in Australia in March 1940. This does not reflect an inexperienced clinician. One possibility is that this Wikipedia author’s view of Geroe’s qualifications has its origin in the Australian entry in the compendium gathered to celebrate the centenary of the International Psychoanalytical Association ( Loewenberg and Thompson 2011). Compiled by the psychoanalyst and scholar Frances Salo using information gathered from available sources, it is stated that Geroe qualified as a psychoanalyst only ‘two years’ before coming to Australia. Following Martin’s account, Salo also states that Ernest Jones, ‘encouraging her migration’, and without necessarily involving the IPA, appointed her as a training analyst. (Salo in Loewenberg and Thompson, 2011, p.346).

A quick check of the International Journal of Psychoanalysis shows that as one a cohort of students who commenced training in 1926, Geroe presented her membership paper on 27 February 1931. She was formally admitted as a ‘full member’ of the Hungarian Psychoanalytical Society on 13 March 1931. (Hermann, 1931, p. 387). In this she was no different than other members of her cohort all of whom presented during 1929 and 1930. Geroe’s was one the last presentations. She had given birth in February 1930, delaying her final paper as a result. I change the Wikipedia entry. The family are pleased. The idea, in Australian circles, that Geroe had qualified only two years before migrating, may be due to a misunderstanding. Geroe was authorized to provide didactic psychoanalytic training to pedagogues in 1938 ( CLG CV 1939, Hermann, reference re Klara Lazar, 20 January 1940).

During her Hungarian years Geroe’s specialty, Pedagogic Psychoanalysis, was developed as a result of her work with the psychologist Pal Ranschburg at the Apponyi Clinic in Budapest while simultaneously undertaking psychoanalytic training. She commenced her training analysis with Michael Balint. By the end of the 1920s she had made contact with Anna Freud and Alice Balint who conducted a seminar for pedagogic psychoanlysts in Budapest. Geroe also attended Anna Freud’s seminars in Vienna. During the 1930s Geroe built experience lecturing parents and teachers. She provided short-term and long-term work for children and parents, as well as conducting an analytic practice with adults. She was one of the analysts working for the Hungarian Society’s Polyclinic in Budapest. In 1933 when Sigmund Freud was compiling a Fetschrift for Sandor Ferenczi’s sixtieth birthday, he invited Geroe to contribute. Her contribution, Nevelési tanácsadás – Educational Counselling, describing several cases of her work with children attending a Polyclinic for ‘The Association of Friends of Children of Hungarian Labourers’, was published in 1933. ( Lazar in Freud 1933). Geroe was, in effect, part of the socialist movement emerging in Red Vienna, and the Free Clinic Movement ( Danto 2012).

One hears her voice in the Ferenczi volume as she argues the case for short term treatment of children who would, otherwise, not be able to reach the help they need. An except from one of the five case study gives a flavour. Translated into English (Google), it reads,

Józsi, 11 years old, 5th grader, father is a baker's assistant, mother is a laundress, only child. His physical development was normal, his habituation to cleanliness was easy, the III. he studied quite well until elementary school, after that he started to decline, lost his way, and missed school for 2 weeks at one time.

On New Year's Eve, his parents left him alone in the evening, then he ran away, spent the night outside the house, when his parents found out about this, he says: ,,k . . . . "aunts" (sic!) wanted to see and listen to what they were talking about. At the same time, he secretly sells small items that he receives as gifts, and sometimes takes small amounts at home. Upon reporting the school, he is sent to foster care, and from there to a boys' home, where he has otitis media diagnosed. It was operated on and he was sent home. Since then, the child's character has been deteriorating, he lies, is dirty, urinates at home and at school, defecates, often and studies very poorly. He is constantly punished both at school and at home, his parents - who used to pamper him and call him names - are now rude to him, especially his father. They beat him a lot; and according to her own admission, his mother often bursts out in anger: "I wouldn't mind if you died!" "I'll kill you if you lie!" etc. The mother cries a lot for her son, who, seeing this, cries with her. According to his mother, the change in the boy's character could have been caused by the fact that they changed apartments and the child got into bad company at school and there is a public house on the street near their new apartment, which excites the child. 2

The boy is small, with a neglected appearance, a very dull facial expression, withdrawn untrusting, indifferent. He appears to be sub-intelligent, answers with difficulty, softly, without colour.

'The question, do you feel good, really surprises you?’, I say to him. ‘It's even more so when I say that I don't think you're having a very good time, because I hear from your parents how bad things are, how much you gets out, both at home and at school. And how would it be good to help it to look different?’

At this, the child loses his previous indifference and begins to cry bitterly. I let him cry, and then I say that he came here to get help, there is no punishment here, this is not a school, patronage or court, the children come here so that if there is no way they can manage something on their own or with their parents, help get He will definitely have such things and we will try to help him! The child sniffs more calmly now, we talk a little more in his own slang, about football, movies, friends, he leaves very relaxed.

There is much more in this case account. Geroe touches goes on to discuss the child’s response to parental neglect and the effect of political tensions between the Social Democrats and Conservatives. She draws on psychoanalytic ideas to explore the child’s relationship with his parents, his curiosity about their activities and also his disturbance that he has not been properly registered with the authorities. This short-term treatment developed by Geroe, possibly follows practices in Vienna and Berlin during the 1930s. She does not claim this work to be psychoanalysis in the formal sense. Yet it is clear that she is well aware of Freud’s theory and is applying it in a particular, focussed way.

It was possible to help the children's problems through understanding parents or through parents' mediation. I could cite many other cases; but I could cite many more cases where, due to parents' opposition, successful analyses failed, or children could not be treated at all. In such cases, analysing the parents could help! The scientific significance and therapeutic safety of the "Educational Counselling" outlined here is far behind that of in-depth, regular child analysis. The importance of this technique is primarily that it was quick help, and it is precisely from its advantages that its disabilities flow. If we take into account these disabilities and our refractory cases, we can still establish the absolute necessity and great social importance of the work in "Educational counselling"." (Lazar in Freud 1933).

Her work at this clinic also seems to be a result of her political beliefs. Her presence at the clinic is advertised in the Democratic Socialist paper, Nepsava. She stands up to government authorities that would close down her clinic, banning children from attending. Democratic Socialists advocated for a different future for worker’s children.

At the Hungarian Society she joined other psychoanalysts in their public education program for parents and teachers.

*******************************************************

Until recently it was believed Geroe’s papers were lost. After her death in Parkville, Melbourne in 1980, the family, with the assistance of her Secretary, ensured Geroe’s case papers were destroyed and her office packed up. With the addition of family and other documents concerning her psychoanalytic training and first decade of her career, her papers were kept by her son at his Castlemaine home until shortly before his death in February 2019.

I had met the family in 2013 several years after I moved to the region in Central Victoria when I approached George Geroe for an interview. Not only was he keen to do this, but he had, for some years, wanted someone to write his mother’s story. He welcomed me into his home on several occasions to view the documents. During 2018 the family placed Geroe’s papers into my safekeeping pending transfer to the State Library of Victoria. This occurred in mid to late 2019. My understanding, at the time of writing, is that the collection is still being catalogued, a process delayed by the Covid pandemic. Read alongside archival material from the British Psychoanalytical Society, Wellcome Library and Freud Museum, as well as Essex University and the State Archives of Canada where the Clifford Scott Papers are held, the Geroe archive is a valuable resource not just for understanding the Australian relationship with the British Centre, but also the work of the Budapest School of Psychoanalysis and the impact of the emergence of Naziism in Europe. Geroe’s Australian story is about the history of psychoanalysis in this country since her arrival. It covers, of course, the formation and development of the Australian Psychoanalytical Society. It is also, at times, extremely harrowing.

*******************************************************

History is inevitably a conversation about the past. It occurs across time and through cultural change. New material is always being discovered. As historians we reckon with sources that might have been manipulated by their originators to tell the story they want heard. Then there is gossip, sometimes called out by correspondents, but often left to take its course. We read these alongside more ‘objective’ evidence: births, deaths, marriages, professional listings, newspaper items about major events listing those present, as well as the official correspondence. We often have only those papers not consigned to the rubbish bin, or like Queen Victoria’s diaries, were edited out of existence – until someone found the originals and a very different story than the starched-up version we had come to know (Bloch 1953; Ward 2014). In these technological days we have access to digitised records which, for a fee, open a past lost to us but for hours of trawling through newspaper and paper archives. We may find sources, like Clara Geroe’s archives, that have been hidden for many years, that challenge accepted, if not beloved, narratives. Those narratives, too, provide food for thought and analysis. In time they can become primary sources in their own right. Frome these we learn how the past informs the present and future.

We can look to the field of Australian settler -indigenous relations as another example of the problems historical subjectivity. Traditionally, self-congratulatory British centred historians have recounted the discovery of Terra Australis and its claim for the homeland. We may know that for centuries the “Great South Land” as it was called and defined as such in relation to Britain and Europe, was little more than a hypothesis. Its dimensions were unknown. The technology enabling shipping vessels to sail so far and so long from the homeland would not be developed until the sixteenth century. The mapmakers drew their maps leaving space for ‘Terra Australis’ surrounded by the four winds – north, south, west and east. It is said to be a long way from anywhere. True enough if we are looking from Britain and Europe. We do not often consider how this land was apprehended by its inhabitants, nor by the people living in lands to the north, or east, of it, in what are now referred to as the Pacific Islands. Their map making and charting of their world is discounted (Perera 2009). The history we make, and write, originated thousands of years ago.

Then there is the recognition by the Australian historian, Peter Read, that the Aboriginal children’s files he was reading in the archive, were the stories of families torn apart by government legislation simply because their parents were Aboriginal (Read 1988). It could not have occurred earlier. The unconscious constraints and restraints of the evolving dominant culture could not allow it. White people accepted, without question, that such policies were correct. Identifiably British, products of a social unconscious that assumed all was right and proper in the British Imperialist world, they did not have the mind to ask questions about Aboriginal child removal policies – although there were those voices who did and were silenced (Aboriginal Welfare 1938). History, written within that frame, reflected it. It is only when one finds a glimpse of another explanation, or a corner, hidden in the shadows of the collective unconscious, suddenly reveals itself, that the historical narrative, if not the paradigm, can change. Read coined the term, “Stolen Generations’, at a point the public was ready to hear it.

When we write or make history, we talk about ourselves, now. The past, if it exists, is somewhere in between now and then, even as we aspire to understand and explore what actually happened and, as Inga Clendinnen put it, make past sensibilities speak (Clendinnen 1996). We must try to live in, and imagine, our subjects’ world to write it. All the while complete understanding is impossible. Historical research sometimes seems like another meeting with one’s countertransference. How one holds oneself in relation to the archive, even when one is bowled over by one horror or another, is to be considered. Building a portrait of a time, place and person is a slow process. History is about entering a field in which my internal matrix, derived from the past of which I am reading, is interacting with it. History is made, somewhere in-between, now and then, present and past.

When it comes to biography, of whom do we speak? It is easy to fall into love, or hate, with one’s subject; or indeed write about ourselves in another’s skin. Biography helps understanding of the past through the window of a person’s life. Through their reactions to their internal and external world we of the present day can learn about our formation. One could accuse oneself of unnecessary prying. And yet we want to learn from our subjects, and about ourselves. The author of a biography has ethical responsibilities to their subject – at the very least checking sources which will, of course have their own limitations (Bloch 1953). Mark McKenna’s biography of the historian Manning Clark outlines the life of someone whose desire was ‘to become a great man’ despite faults and difficulties he did not much like. Some might call Clark narcissistic. McKenna does not criticise. Instead, he reveals a desolated core that did not dissolve despite Clark’s very real achievements and contributions to Australian historiography (Mc Kenna 2011).

Linda Hopkins’ work on Masud Khan (Hopkins, 2006) similarly addresses the flaws that derailed a deeply talented man. She sets these alongside his accomplishments without rancour. ‘Mini biographies’ emerge of Anna Freud, Winnicott, and other people surrounding Khan. Perhaps unwittingly they may have complicit in his tragedy. My reading is to wonder whether the lack of understanding of what it might have meant to be oriental in Britain contributed to Khan’s downfall. Or is it another version of colonialism in action, as it contours emerge from the darkness of the Imperialist social unconscious. Hindsight can be cruel, particularly when it reflects against us. It also warns against hagiography.

In writing about Clara Geroe, a woman who I had never met, known to me only because I work in a similar field, I came with few suppositions – or at least the impression that she did not stand for the psychoanalysis that everyone was practising. I have been surprised and delighted by what I have discovered, even if I don’t always agree. Yet I must write with understanding about her work combining the roles of analyst and supervisor of analytic candidates; investigating the reasons behind it. And if there were boundary transgressions for some, I must also understand that such events did not affect everyone in the same way. I learn that there are many versions of Clara Geroe – and practices that I would not endorse or follow.

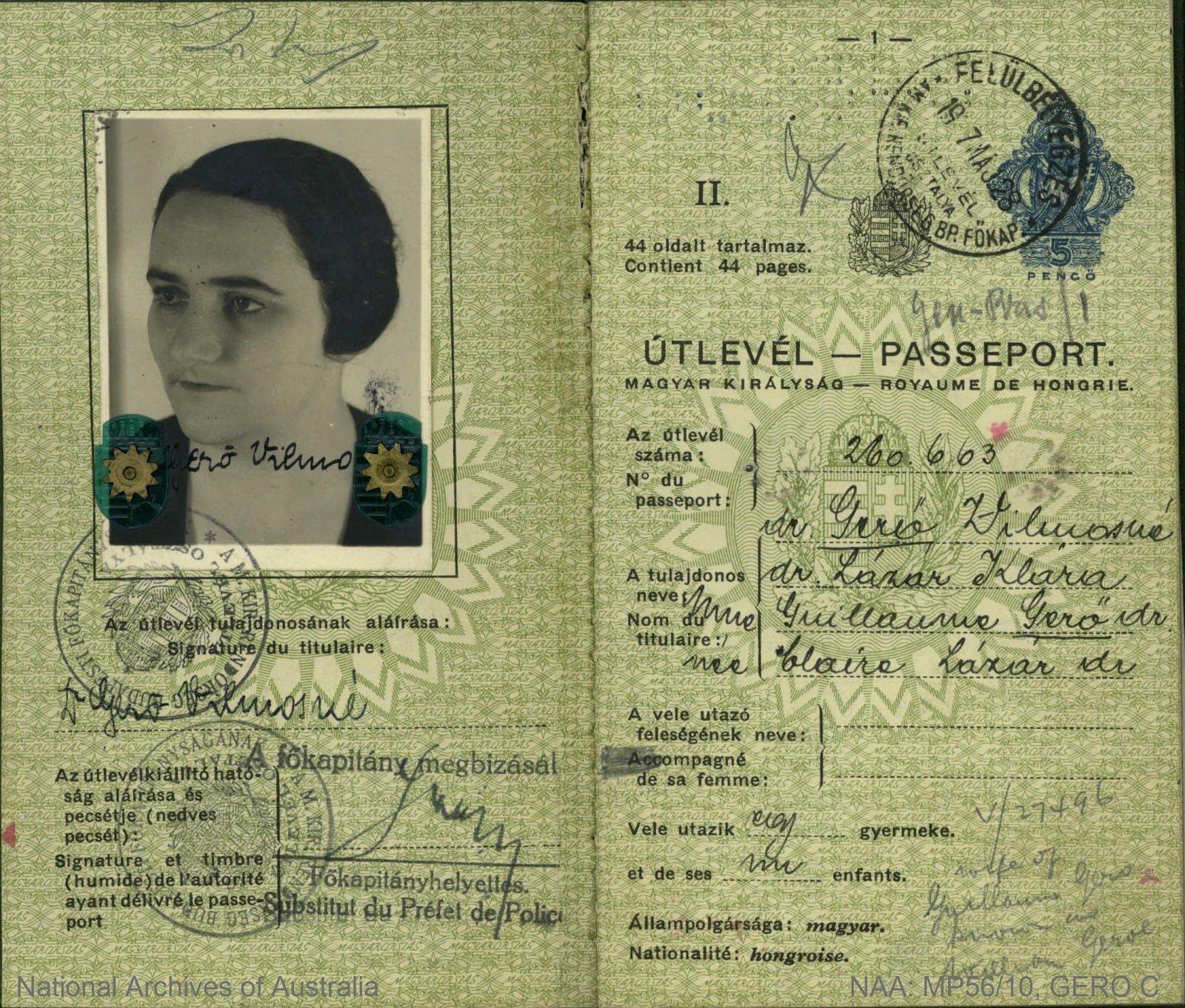

So, to another portrait. While writing my paper for the IPA Pacific Rim Conference in 2024 I was reading Dierdre Moore’s account of her analysis with Geroe (Moore 1999). I have read this paper numerous times, absorbing Moore’s description of Geroe’s consulting room with its Persian carpets and luscious embroidered cushions from Central Europe. This is 1940s British Australia when refugees were suspect, often imagined to be Fifth Columnists, working for the enemy. Moore could not know that Geroe had had her passport confiscated by a suspicious immigration official when she landed in Fremantle on her way to Melbourne in March 1940. It is clear, on reviewing the passport, now digitised in the National Archives website, that she had travelled extensively and alone throughout (enemy) European countries since it was issued in 1937. Would this have explained an Australian Official’s suspicion? I wondered. Vilmos Gero did not have to relinquish his documents. Without a passport, reliant on her husband’s immigration papers for her status, Geroe faced deportation should she be considered to be out of line with the rules. Moore would not have been entirely aware of the restrictions placed on Geroe’s movements – as with other refugees, although she would have read the newspapers of the day. In 1942 Geroe and her husband were refused permission to purchase the house they had spotted because they were ‘enemy aliens’ (9 July 1941, NAA:12217, l5867). Like it or not in the early 1940s Geroe’s future in Australia was tied to her employment at the Institute. That her analyst had few rights of her own were not Moore’s concerns. Yet one wonders how this may have affected the dynamics of the analysis and the analytic space?

Through reading Moore’s account I have imagined Geroe’s accent and identified with Moore’s indignation at being confronted with the reality of her mind. What would SHE know? I hear Moore thinking. Or is this my question? It is hard to shuffle off accounts of Geroe which give short shift to Hungarian ways that Australians have long relinquished (Martin 1995, Salo 2011). In Moore’s paper, if we read carefully, we also learn of Geroe’s commitment to her task. She too has had to face the questions she asked of Moore and had found a different answer.

The décor in Geroe’s consulting room is so different to anything Moore had experienced in her middle-class Australian childhood. I begin to realize that her description exoticizes the culturally different Hungarian woman who is her analyst. It seems that as a member of British culture, her right to do so is assumed. In his 1978 work “Orientalism’ scholar and historian Edward Said suggests it may be. Said’s critique of the colonialist mentality that rebukes and diminishes the other for their difference has become a seminal text. The oriental object holds projections of those parts of the self that are disavowed, archaic and instinctual, and in some instances, erotic. Said reminds readers of scholarship examining and recasting the subaltern voice as witness to its plight by removing the muffles of colonialist commentary. Clearly Geroe was not a colonial subject in Said’s original terms. However refugee status denoted a kind of exoticism and non-Britishness in the eyes and ears of the dominant culture, diminishing her humanity

Image: GERO Claire [Dr] [and child] - Nationality: Hungarian, NAA: MP56/10, Gero C National Archives of Australia.

For most of the twentieth century, up until the 1970s Australians were considered ‘British’. Schoolchildren were honouring the Queen of England; the Union Jack took pride of place alongside the Southern Cross with the Union Jack neatly sewn into the top left-hand corner. The historian Neville Meaney points out, that Britishness was imagined to be correct and superior, a view deeply imbibed into the psyche of Australians’ minds (Meaney 2001). Moore’s paper, published in 1999, almost half a century after the events she describes, appeared less than four years after Martin’s claim, in 1995, that Australian psychoanalysis was now ‘British’. Any sign of its Hungarian origins were now ‘nowhere to be encountered’ (Martin in Kutter1995, p. 37). It seems Moore assumed that British and Australian readers would share her response to Geroe’s rooms. Klara Geroe, still mourning the loss of her homeland, and privately railing at her situation, and the fate of her family following the Arrow Cross terrors in Budapest, may not have apprehended Moore’s response to her, a foreign refugee in a singularly British- Australian society (Geroe to Anna Freud, draft 26 March 1946).

The Geroe family decided to emigrate to Australia following the failure of their New Zealand application in December 1938. There is no archival evidence or comment about any wish to migrate to either Britain or the United States. New Zealand was her husband’s wish – he was an outdoors man, a lover of the Austrian Alps. Images of similar landscapes in New Zealand had drawn his interest. ( George Geroe 23 August 2013). Vilmos Gero had also been the target of Fascist Brownshirt attacks during hiking expeditions. In line for promotion at his workplace, he had been passed over because he was Jewish ( Rena Geroe, email 25 February 2024), Geroe was opposed to the idea of migration. Some friends prevailed upon Vilmos to cease his senseless plan. But Vilmos was adamant. Geroe’s family respected his judgement. Both the couple wanted a future for their son. And once persuaded, Geroe wrote the necessary letters and filled in the application forms and sought help from Ernest Jones.

Granted a visa for Australia in July 1939 the family left Budapest by train in early January 1940 and set sail from Genoa on the motorship Viminale on 20 January 1940. One of a fleet of four owned by an Italian company, the Viminale had ferried migrants from Greece, Italy and Southern Europe to Australia since 1930. The Geroe family’s original intention was to settle in Sydney. They appear to have diverted this plan upon hearing from Ernest Jones of plans to establish an Institute of Psychoanalysis in Melbourne. When they arrived on an extremely hot day on 14 March 1940, the smoke from bushfires surrounding the city was apparent. Dr Paul Dane the driver behind the development of the Melbourne based psychoanalytic clinic met them at the docks and drove to their accommodation, a boarding house in St Kilda, Melbourne (G Geroe 26 August 2013).

After arriving in Melbourne Geroe discovered that the Institute project was in doubt because the donor, Lorna Traill, the daughter of the coastal shipping magnate, John Traill, had withdrawn her offer of funds for an Institute. She had originally promised funds amounting to five thousand pounds. For almost six months it looked as if the Institute would not happen. Roy Coupland Winn, Australia’s first practising medical psychoanalyst, an Associate of the British Psychoanalytical Society offered to accommodate her in Sydney (Winn to Geroe 17 July 1940). Geroe was tempted. However she felt morally obliged to remain in Melbourne while Dane tried to persuade Traill to reconsider. She also felt a debt of gratitude to Ernest Jones who was backing the proposed Institute. (CLG to Winn August 1940 notebooks 1940). Traill finally provided a thousand pounds plus another five hundred if the institute was opened on her birthday – October 11, 1940 (CLG to Winn, c, August 1940, draft, notebooks). This amount was not enough to continue the original plan for an ‘Australian Institute of Psychoanalysis’, Geroe wrote apologetically to Winn. It would have to be the ‘Melbourne Institute of Psychoanalysis’. Sydney would have to wait. The Melbourne Institute of Psychoanalysis at 111 Collins Street Melbourne was launched on 11 October 1940. It formally opened its doors for business on 15 January 1941.

Developing the nascent organisation was hard work. Geroe’s notebooks show she fought numerous battles with Dane during 1940. Early on Dane prevented her from writing to Jones – her main support person - when he realised funds had been withdrawn. He was angered that Geroe declined to take him on as a patient, despite her explanation that their connection and professional relationship mitigated against it ( CLG to Jones, c. May 1940, draft, notebooks). Most importantly Geroe was utterly dismayed when she discovered that despite Jones’s original advice to Dane that he connect with the IPA Training Secretary Eitington in Jerusalem, Dane had not done so. Nor was he going to. (Jones to Dane 11 September 1939 BPAS Archives G07/BH/FO1/47). Geroe’s notebooks from the months from April to December 1940 indicate Dane had told her that any question of an IPA connection was not her business, that she was only an employee of the Institute. She tried to appeal to Roy Coupland Winn, Australia’s first practising medical psychoanalyst and an Associate Member of the British Psychoanalytic Association, to intervene, using his membership as leverage (Geroe to Winn, draft April/May 1940, notebooks). To no avail. The best she could do was to ensure that a statement about her commitment to meeting IPA standards of training was included in her contract.

Then there was the matter of becoming a training analyst. One guesses that after an approach for training by Dr Frank Graham in early 1941, her notebooks suggest that she wrote to Jones asking she be appointed as a ‘Lehrenanalyse’. She was appointed as a Full Member of the British Psychoanalytical Society and as a Training Analyst at the Society’s Annual General Meeting on 9 July 1941 (S-A-3-A-1(AGM). This was just over ten years after her formal acceptance as a full member of the Hungarian Psychoanalytical Society, and fifteen months after her arrival in Australia. There is no indication in the material, so far located, that Geroe was sent to Australia by Jones or encouraged to do so with the promise of becoming a training analyst. At this time Jones also had connections with newly forming organisations in Southern America which, shortly after the arrival of the migrant analysts, affiliated with the IPA. Several were made component members of the IPA in 1949, the year Jones retired ( See Loewenberg and Thompson 2011).

A draft letter from Geroe to Anna Freud, dated 26 March 1946 outlines the dimensions and the harrowing nature of her difficulties with Dane during the first five to six years of the Institute’s life. This was a mix of his support, and then his antipathy toward her; antagonism towards psychoanalysis, his demands for his own treatment, which she refused, and then the treatment of a family member which she was not able to turn down despite her wish to do so; his defensiveness, and finally his move to close down the Institute in 1945, pleading financial difficulties. As a refugee in the 1940s Geroe was reliant on Dane’s good will. She was aware that should she not comply and lose his support she and her family would be in considerable difficulty. It did not stop her trying, certainly when it came to treating either him or a family member. Geroe also desperately wanted another analyst to come to Australia. She worried about the students not having access to the diversity of ideas and contemporary developments and debates. She did not see herself as a theorist. Rather, like the Budapest psychoanalyst Vilmas Kovacs, she was a sound but not innovative clinician. Without access to a psychoanalytic community she felt her own lack of development acutely. Her isolation and despair, exacerbated by Australian war time conditions, was deeply distressing for her. She was deeply ashamed, she wrote to Anna Freud, that she had not apprehended the situation clearly enough earlier. The result was that she had withdrawn from the very support she had needed, by not writing to Anna Freud. When at last Anna Freud reached out and asked how she was faring, Geroe’s response, a long rambling draft of a letter surely contains the anguish of years. Without a community, support, and the prospect of another analyst more and more a distant hope, Geroe was, she said, ‘very very lonely’ (Geroe to Anna Freud, draft 26 March 1946). In the face of Dane’s decision to close the Institute down Geroe’s undertaking to underwrite the Institute financially, thus keeping the Institute solvent, was accepted by the Institute’s Board.

*************************************************

By 1949 Geroe had trained two psychoanalysts to independent practice: Dr Frank Graham who was Melbourne based and Dr Harry Southwood from Adelaide. Another candidate, Albert Phillips was continuing his training. So too was Arthur Meadows a psychologist from the Children’s Court Clinic and Janet Neild. Dr Rose Rothfield was also training. Dierdre Moore discontinued training after deciding to move to Tasmania with her husband. Southwood’s training was ‘experimental’ Geroe wrote in 1950 ( CLG Report to Rickman 25 June 1950). He travelled from Adelaide to stay in Melbourne either for months at a time, or as the years passed, for weekly and fortnightly visits. He had analytic sessions in the morning, supervision in the afternoons. We may wonder about the nature of the experimentation occurring in Budapest, if not Viennese circles.

*****************************************************

1949 also featured the arrival of a second psychoanalyst in Australia. Geroe’s Hungarian colleague Endre (Andrew) Peto had originally applied for an Australia visa in 1939, at the same time as the Geroe family, The woman who became his wife, the psychoanalyst Elizabeth Kardos, also applied. Although all their applications were successful Peto and Kardos had not taken up their visas. Kardos, who had fought for the Australian application to proceed, also decided to remain in Hungary (Vickers, forthcoming). She and Peto married in 1940. In December 1946, two years after Kardos’s death, Peto applied again for Australia. By the time his visa was granted he had married again, this time to Hannah. She had brought her daughter Agi into the marriage. Upon arriving in Melbourne on 12 September 1949, Peto was taken in by his colleague and friend Klara Lazar Geroe.

Peto arrived in Australia as a displaced person after the dissolution of the Hungarian Psychoanalytical Society in 1948 when the Soviet Union took control of Hungary. Up until then he was the Society’s Secretary collaborating with the psychoanalysts Imre Hermann, Istvan Hollos, Kata Levy and Lilly Hajdu. All of them had survived the catastrophic invasion by Hitler’s and the atrocities of the Arrow Cross in 1944 -45. Andrew Peto’s wife Elizabeth Kardos had not. When the Nazis arrived in October 1944, the couple went into hiding separately. Every few days Kardos would take food to her husband. Someone denounced her, the historian Anna Borgos says. “Neurologist Margit Ormos recalled that she had met her at the gate to the ghetto in January 1945. She had a bag in her hand, perhaps was fleeing from somewhere or went to help someone. She was most likely the last person who saw her.” (Nemes in Borgos 2022, p. 25, 149).

Michael Balint

Anna Freud

Vilma Kovacs

Alice Balint

For Kovacs and Michael Balint the analyst was best positioned to work with the candidate/patient’s countertransference to free them from undue interference in the unfolding analytic process with their own patients (Kovacs, 1936). This method was followed by Balint well into the 1950s. He came to an arrangement with the British Psychoanalytical Society that who wished to train with him were obliged to undertake and additional supervisory case. It was over the matter of the conduct of the training and control analysis, resources and conditions, that the Australian group collided with the British.

By 1950 Peto had moved to Sydney’s Bellevue Hill and begun to establish his practice. On 25 June 1950 Geroe approached John Rickman in London seeking to raise ‘the question of the formation of an official psycho-analytical Society in Australia’. She asked that the matter be dealt with by Council ‘while you (Rickman) are still Chairman, as it was Dr Jones and yourself who helped us to kindly at these early stages of the organisation of our Melbourne Institute.’ She also asked that Winn be made a Full Member of the British Society and some sort of gesture be made towards Dane who, despite his interest and at times, antipathy towards psychoanalysis, was not a psychoanalyst, had contributed much to the development of the Institute. (Geroe to Rickman 25 June 1950 BPAS G07/BH/FO2/05).

BPAS indexes show that Geroe’s proposal, worded in terms of the Australian group becoming a Branch was considered at the Society’s Board meeting on 19 July 1950 (BPAS S-A 2-1). It appears Peto had sent a proposal to London at the same time as Geroe. The wording of the BPAS listing is ‘Dr Peto’s proposal for the Australian Study Group to be made a branch of the BPS’ was discussed ( BPAS S-A-4-3) ( My emphases). We don’t know the circumstances of this, nor why both Geroe and Peto sent such correspondence on the same topic. To date, archival records have not revealed the actual correspondence from Peto.

Peto was highly active in his early years in Australia. He taught psychoanalytic ideas to psychiatric registrars, wrote articles for the Medical Journal of Australia and was a leading figure in the Asia Pacific Child Development Conference in 1953. In 1951, the Sydney Institute of Psychoanalysis was formed with funding from Roy Coupland Winn. The Australian Association of Psychoanalysts was formed in December 1952. By this time both Frank Graham and another of Geroe’s trainees, Harry Southwood were Associate Members of the British Psychoanalytical Society. Roy Winn was ratified as a Full Member with the provision that he did not train others. A third psychoanalyst Ivy Bennett who had returned to Australia to practice in Perth after training with Anna Freud had been elected as an Associate Member of BPS in 1952. She too was a founding member of the new organisation. Still, the Medical Board rejected Peto’s application for accreditation as a Medical Practitioner in Australia.

IMAGE FROM ASIA PACIFIC CONFERENCE 1953 NAA: A1805, CU18/10 (National Archives of Australia).

L to R: Dr Elwyn Morey, Mr Eric Troy, Dr Naomi Ryan, Dr Stanley Mirams, Dr Hariati, Dr David Jackson, Dr Andrew Peto, Mrs Luisa Alvarez [photographic image] / photographer, John Tanner.

Devastatingly for the struggling group in early 1956, Peto received his United States Visa. According to Lawrence Nield, the son of the early analyst, Janet Neild, Andrew Peto had always intended to emigrate to the United States (L Neild, conversation with the author September 2018). It is not impossible that he may have stayed had the Medical Board seen fit to allow his registration. After some seven years with two fully qualified analysts practising and training the Australian group was again without a second training analyst. The death of Maida Hall further crippled the Sydney Institute’s viability.

For Geroe, whose first decade in Australia as the sole fully trained psychoanalyst, charged with the task of creating a psychoanalytic training, Peto’s departure was extremely difficult. During the first decade of the Melbourne Institute’s life, she had fought for the survival of the Institute despite continuing difficulties with Dane, including his move to close it down. Peto’s arrival and the subsequent launch of the AAP and SIP both supported by Michael Balint as a liaison person in London would have been gratifying. Both Southwood and Graham as well as a third trainee, Janet Neild, applied for Associate Membership of the British Society. However Rickman’s sudden death in 1951, followed by the appointment of Donald Winnicott as the Training Secretary, changed the dynamic of the relations between Australia and the British Centre. No correspondence formally acknowledging Australia’s status in relation to Britain has come to hand. Letters from Winnicott to Geroe refer to the Australian group as a ‘Branch’. It is and was very confusing.

During the mid 1950s it became clear that Winnicott was unwilling to make concessions to the pioneering nature of the Australian group Rickman and Jones had. Perhaps he did not see the need. Furthermore the nature of psychoanalytic training had undergone significant revision during the 1940s. Neild’s application for Associate status was not accepted. Southwood was obliged to resubmit and later became an Associate in 1953. Graham became an Associate in 1952. Matters came to a head when Dr Rose Rothfield received a letter from the BPS Training Committee dated 27 September 1956 rejecting her application for Associate Membership. Training regulations, it was stated, ‘required that the supervision of clinical work must be done by an analyst other than the analyst who undertakes the personal. The Training Committee proposed that Peto supervise Rothfield for an additional case and send a report when it was completed. This would enable Rothfield’s admission (Heimann to Rothfield 27 September 1956).

To say that Geroe was gobsmacked would be an understatement. No formal advice of any change of policy had been communicated to Australia. Despite their efforts the British Centre members did not understand the realities of distance faced by the Australian group. (Geroe to Heimann, draft October1956). Peto had just left the country. While Rothfield was passed after it was established that she had received supervision from Peto as well as Geroe, the British continued to insist that the rules were the rules and that they had made a significant compromise allowing Geroe to supervise as well as analyse.

In response Geroe fought for the future of the Australian training. She drafted and redrafted her letter. Broadly, she made the following points. Her single-handed role in the Australian training was known to the London training Committee. Drs Jones, Rickman, Balint and Miss Freud were aware of it. She had corresponded with Rickman and Balint in 1948-9. (Geroe to Heimann and Hoffer 30 October 1956). Geroe wrote in protest:

A rigid adherence on the part of the Training Committee to the principles of different training and control analysts would, of course, cut off for some time at least any training in Australia and would cause us to lose a few adherents and supporters the analytic movement has in this country. What this means to me personally I don’t think I need to emphasize’ ( ibid).

The real solution, she continued, ‘was for another training analyst to settle here’. She had said this before, to Anna Freud, and most likely to Rickman as well as Balint and Jones. Peto was almost gone. ‘We are going to lose soon, Ivy Bennett’. Bennett was heading to England for more training and a job at Anna Freud’s clinic. ‘The departure of these two may indicate to you also the unpleasant atmosphere and difficulties which our movement has had to face… There is no place in this letter for describing the frustrating atmosphere with which our group struggles’. ( Note on draft letter to Paula Heimann 30 October 1956).

By then President of the British psychoanalytical Society, Donald Winnicott was unsympathetic. It is not clear why Janet Neild requested that Winnicott review a case study she had just completed. She had had her own difficulties with Peto who had taken over her training after her move to Sydney in the early 1950s. While Winnicott considered work to of be sound quality, he wrote to her on 29 November 1956, ‘you yourself have not been able to undertake the psychoanalytic training’ – by which he meant the British one – ‘and therefore however good your work, it is not possible for the Institute of Psychoanalysis to give you the qualification of child analyst’. Neild, he continued, would

‘agree with the very uncomfortable fact that there is in Australia not a sufficient training team to justify the term ‘psychoanalysis’ which has to be jealously guarded. You would understand this better if you knew, as I do, the dangers to psychoanalysis that exist through the watering down of the training scheme.’ ( Winnicott to Neild 29 November 1956).

Winnicott also wrote to Geroe on 29 November 1956, acknowledging his letter to Neild and adding his views on the problem of distance.

‘I would like to point out that the problem [of distance] is just as acute as if we were to talk about Liverpool – we do not need to go several thousands of miles away to Australia. There is a need for psychoanalysts in Liverpool. At the present moment, however, there is no way of getting a psychoanalytic training ecept in London in this country and in the end there would be no gain from setting up a training scheme in the provinces with the lowering standards. Over time, psychoanalysis will go out of London into the provinces, but in the meantime, we must continue to say even Cambridge is too far away’.

Nothing Geroe said made any difference. A letter from the Training Committee arrived in early January 1957. Signed by John Bowlby then the Secretary of Training it withdrew accreditation of the Australian Training (Bowlby to Geroe 27 December 1956, BPAS G07/BH/FO1/23).

In response to Geroe’s appeal Bowlby, brokered a compromise. He arranged that Graham and Southwood, both Associate members of the Society could go to London and qualify as training analysts. After their return the Australian training was restored in 1960, contingent upon continued consultation with the British Centre and candidate’s presentation of a paper to the Society. It means that there was, in effect, more than one analyst doing the analysis, supervision and accreditation. A secondary effect was that the Hungarian dominance of the Australian training was significantly watered down and anglicised. The Melbourne and Adelaide groups were granted permission to continue with the trainees already underway. In future years the sense that Melbourne was continuing training while Sydney was left behind remained a source of grievance and antipathy for the Sydney analysts.

It could have been so much different. Had Geroe discussed the matter with her protegees among the Australian group, Graham and Southwood as well as Winn some different strategies might have emerged. She would have at least had more support. Perhaps a misplaced sense of analytic discretion prevented her from doing so. She was their analyst and teacher. It appears that she withdrew, bundling up the Rothfield correspondence with the British Centre, and locking it away in the cupboards of her home and mind. She held the matter, alone.

In 1965 the Council of the British Psychoanalytical Society realised ‘that in conducting training outside its territory in Australia it was not acting in accordance with the regulations of the IPA’. Even though, Council wrote, the Australian members had ‘called themselves a branch of the Society and believed they had a corporate existence in the eyes of the IPA’ this was, in fact, not so. They were Members of the British Society resident in Australia, (BPAS Statement, 1 March 1967, SA/IPA/A/5,Wellcome Library).

Unravelling Geroe’s story and the history of the Australian psychoanalytic project continues. Its fabric, an interweaving pattern of migration, dislocation, imperialism, hope, personal tragedy, politics and ambition, is complex and insufficiently understood. Questions about authority and the nature of psychoanalysis –jostle with interpretations about Geroe’s demeanour, competence, and tensions between the Hungarian and British Schools. This history has also contributed to the development of other psychoanalytic groups, particularly during the 1970s when the Australian Psychoanalytical Society was launched.

It has been said that Geroe was traumatised by her war experiences in Hungary and that this might explain her propensity to be controlling ( Salo p. 348). In fact, Geroe escaped the worst of it. She was long gone from Hungary when Hitler invaded in 1944 and used the fascist group, the Arrow Cross, to destroy the Jewish population. Nevertheless, the issue of Geroe’s ‘controlling’ ways, and even her own trauma, need to be addressed. There is the nature of Geroe’s demeanour. George Geroe says his mother did not often ‘have adventures.’. It was hard for Geroe to bring herself to spontaneous activity, her husband implies. Her schoolfriend and, for a time, fiancé, Arthur Linksz remarks on her coolness and at times, her lack of sentiment. Yet he held her in high esteem loved her deeply. He was devastated when, during their student years, she decided that ‘she could not return [his] love’ (Linksz 1986). Linksz immigrated to the United States in 1938. He became world renowned as an ophthalmologist and author. The two always kept in touch. Geroe was serious, conscientious, and more than once rebuked by her sisters for her failure to communicate. She herself acknowledged her propensity to retreat into silence, often for long periods, when she was confused, or not coping with a difficult situation. Perhaps, purely speculatively, part of her apparent controlling ways were connected to the ‘knocks’ she received from the British Centre. There might have been one or two, too many.

Geroe’s letters to Anna Freud and to Ernest Jones reveal another side of her humanity – a deeply passionate, emotionally aware - if not too self-disclosing - woman. She laboured to put feelings and words on paper, although she said, she could write analytically without any trouble. Geroe was the youngest in the family – an ‘afterthought’, her granddaughter notes. During her childhood was often alone, spending time with the servants for company, her son reports. Her sisters, ten and twelve years older than her, were busy with their lives, as was her mother, a leading figure in the provincial Hungarian Town of Papa. Geroe was also very determined to achieve her objectives – appearing unemotional on the outside, deeply observant of the goings on about her, responding all the while but holding herself together for the main goal. A strategist, charming, and wily: all are words that are used about her. She appeared to have enjoyed a good argument with her husband, perhaps one of the few people with whom she could relax enough to do so. There is much to learn about this woman who found herself at the centre of Australian Psychoanalysis after a very reluctant migration ( C Geroe 1982).

*********************************************

Geroe’s family kept her archive, untouched for forty years. It was one way of holding her voice close, protecting her, healing from the talk and events that had also affected their family. Now, at last, and certainly when her papers they are finally catalogued, we can find many other aspects of Geroe’s life and career. There are her public lectures during the war years when she speaks to parents and teachers about their children. She tells them in plain language about the value of steady ongoing parental presence for children in traumatic situations. She draws on Ferenczi’s ideas about child development, and also Alice Balint’s theoretical contributions published in her small book. The Psychoanalysis of the Nursery, as well as from Anna Freud (KLG lectures 1940s). And slowly we can learn of her psychoanalytic career in Hungary including her socialist ideas reflected in her work with the children of Hungary’s labourers.

Geroe’s influence in Australia is found in quarters other than the institutes and associations practising psychoanalytic therapy that have emerged in the last fifty years or more. A 1953 article published in the Australian Women’s Weekly, which extolls the value of parents’ presence for children in hospital (AWW November 25, 1953, p.20) most likely has its origins in Geroe’s connection with the Hospital. She lectured at the experimental Koornung School and was an advisor at its sister, Preshil School. She attended New Education Fellowship Conferences and lectured to the Children’s Court workers. All her letters, lectures, talks conversations, were written by hand, corrected and recorrected, before the final despatch to the typist, if there was one. Otherwise, she did this work, too. One is impressed by her constraint. She often held herself back, keeping her silence amid what seemed to be mayhem. Only her family knew her feelings. Geroe’s struggle to establish and sustain a project begun in the service of the International psychoanalytic project, was not only heroic but perhaps, accidental. As she said of herself, she was a reluctant immigrant. Geroe may have believed she had few choices other than to immigrate, and in Australia, to stay with the Institute if she and her family were to survive. Perhaps this is part of the trauma at the centre of Australian Psychoanalytic project.

References

Aboriginal Welfare (1938), National Archives of Australia.

Archives of the British Psychoanalytical Society.

Bloch, M (1953), The historian’s craft, New York, Knopf.

Borgos, A (2022), Women in the Budapest School of Psychoanalysis: Girls of tomorrow, London, Routledge.

Clendinnen, I (1996), Fellow sufferers, history and the imagination, Australian Humanities Review, Issue 03, September 1996. Online.

Geroe, C (1982), A Reluctant Immigrant, Meanjin 3/1982, pp. 352-357.

Geroe, KL Papers. 1920s- 1980. Originals State Library of Victoria, to be catalogued. Copies held by Author.

Geroe, G (2013), Interview with Christine B Vickers, Full copy in possession of the author. Abridged copy on Psychoanalysis Downunder 2014.

International Psychoanalytical Association – Australian Psychoanalytical Society 1949-1999, SA/IPA/5, Wellcome Library.

Hermann, I (1931), Report of the Hungarian Psychoanalytical Society, International Journal of Psychoanalysis, p. 387.

Hooke, M T (2010), The Tyranny of Distance: the early history of APAS, Psychoanalysis Downunder #10.

Hopkins, L (2006), False Self: the life of Masud Khan, London, Karnac.

Kovacs, V (1936), Training and control analysis, International Journal of Psychoanalysis, 17, 346-354.

Linksz, A (1986), Fighting the third death, New York, Privately published.

Lowy, C (2005), Losing Brancusi, Meanjin, 64 (1-2) 60-65.

Martin, R ( 1995), Australia in Kutter, P. (ed.), ( 1995) Psychoanalysis International: a guide to psychoanalysis throughout the world, Vol.2, America, Asia, Australia Further European Countries, Stuttgart-bad, Frommann-Holzboog.

McKenna, M ( 2011). An eye for eternity: the life of Manning Clark ) 2nd edition, Carlton, The Miegunyah Press.

Meaney, N ( 2001), Britishness and Australian Identity: the problem if nationalism in Australian history and historiography, Australian Historical Studies, 32:116, 76-90, DOI: 10.1080/10314610108596148

Meszaros, J (2013), Ferenczi and beyond: exile of the Budapest School and Solidarity in the psychoanalytic movement during the Nazi Years, London, Routledge.

Moore, D ( 1999), A memoir of my psychoanalysis with Dr Clara Geroe, British Journal of Psychotherapy 16(1): 74-80.

Peto, A (1981), Notes on the life of Clara Geroe for her memorial service, copy in author’s hands.

Read, P (1988), A hundred years war: the Wiradjuri people and the state, Sydney, Australian National University Press.

Sick children need parents at their bedside (1953, November 25). The Australian Women's Weekly (1933 - 1982), p. 20. Retrieved February 18, 2024, from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article41447234

Ward, Y M (2014), Censoring Queen Victoria: how two Victorian gentlemen edited a Queen and created an Icon, London, Oneworld.

W and C Geroe -Purchase of property, Vic, NAA: A12217, L5867, item ID, 5449523, National Archives of Australia.