Loss Across the Lifespan - Mourning and Melancholia in Couples

Timothy Keogh

APAS 50th Anniversary Conference 2023

Introduction

In the poem Home Burial Robert Frost (1914) writes poetry which is reminiscent of a scene from a play by virtue of Frost’s clever use of blank verse or unrhymed pentameters. It provides a unique depiction of an interaction between a couple who display signs of unremitting or prolonged grief. The poem opens with the wife at the top of a staircase looking at their child’s grave through a window. At the bottom of the stairs, her husband struggles to understand what she is looking at or why she has suddenly become so distressed. The husband asks:

'What is it you see?

From up there always - for I want to know.’

His wife resents what she perceives as her husband’s lack of concern about the death of their child. He pleads with her to stay and talk to him about her grief. He does not understand why she is angry with him for expressing his grief in a way different to her.

‘My words are nearly always an offense.

I don’t know how to speak of anything.

So as to please you.’

Her husband in desperate state to get through to his wife says:

‘Let me into your grief. I’m not so much

Unlike other folks as your standing there

Apart would make me out.

Give me my chance.’

This poem captures the dilemma of many couples struggling to understand their own and each other’s grief. In psychoanalysis unresolved loss, historically known as melancholia, is seen as a psychic constellation wherein normal mourning is attenuated and where instead a pathology develops such that the bereaved is increasingly in a tormented state, pining for the lost love object and caught in feelings of self-reproach.

Such psychopathology has been the subject of great interest in mental health research in the last couple of decades, studied under the designation of complicated or prolonged grief. Clinicians and theorists including Neimeyer (2002, 2008), Parkes (1972), Kubler Ross (1970), Prigerson et al (1995, 1999), Shear & Shair (2005) and Stroebe & Schut (2005) have added greatly to an understanding that unremitting grief is a unique pathology and psychic experience so that this pathology is now seen as a distinct diagnostic entity. Ultimately, Prolonged Grief has been accepted as a diagnostic category in the DSM-V-TR edition released in 2022.

I note that many of the diagnostic features described are linked to original psychoanalytic formulations concerning failed mourning.

Psychoanalytically speaking, the ability to mourn is inextricably linked with a capacity to psychically differentiate ourselves from the other, initially our primary object of attachment usually the mother. Having said this, given that psychic development is not linear but dynamic, under stress everyone is prone to regression and to experience the pain associated with such disintegrated modes of experience.

When it comes to couples, previous unmourned losses can significantly add to the grief associated with the loss of a baby or a young child, making it a more chronically painful and unrelenting experience. The couple relationship under the aegis of regression can become the scene of painful unconscious re-enactments of the sequalae of unresolved loss, particularly in relationship to self-reproach and persecutory guilt.

For clinicians faced with such couple presentations psychoanalytic theory provides a very valuable contribution to understanding the states of mind associated with unresolved loss.

Psychodynamic views about loss

Freud’s (1917) original notion about unremitting grief expounded in Mourning and Melancholia was that where a struggle with mourning turns into an illness, it is related to underpinning narcissistic difficulties and associated ambivalence toward lost attachment figures. He saw that melancholia, in contrast to normal mourning, resulted in an unremitting emotional suffering and misery and, in extreme cases, the risk of suicide (which he saw as related to substantial unconscious sadistic impulses towards the lost loved object). He posited that relatedly the superego takes on a more primitive form, making the experience of it more like a severe internal judge.

Freud felt that for the mourner it is the loss of the object that is at the centre of the experience, whereas in melancholia it is the loss of a part of oneself due to the narcissistic identification with the lost object. He thus emphasised the lack of individuation and separation from the object.

In explaining these phenomena, Freud (1917) for the first time made another important discovery which was that the ego could split, and aspects of the self could be projected onto the “other” with whom he is unconsciously identified.

Klein (1945) was able to enlarge our understanding of the mourning process. As will be elaborated in Sonia Wechsler’s paper, she proposed that a baby is initially in a state of un-integration and comes to a state of integration only painfully by negotiating its emotional experiences with an object (other) that is initially seen to be part of itself, but from which it is gradually able to separate.

For Klein the major signposts of a dynamic, non-linear mental development were psychic positions or modes of psychic experience from which even integrated, healthy individuals could temporarily regress when under stress. In particular, she described a mode of experience where a baby is in a state of unintegration or disintegration as the paranoid-schizoid (PS) position. This was seen to result from the baby’s inevitable frustrations in its relationship with its primary attachment object (usually its mother). In order to cope with these frustrations, she felt that the infant needed to split its object into two psychic representations (one good and one bad) that were kept separate from each other. These become internalised objects and are seen as identical to the external object (mother). In this sense one can see how important the quality of the actual mothering, or how the handling of the transference is, in the process of structuring such representations.

Klein echoed the observations of Freud in Mourning and Melancholia that, at the same time as the object is split, so too is the ego (self). For Klein the conclusion was that there are consequently split-off parts of the self in relation to split parts of the object. This is, of course, the basis of object relations theory.

The splitting of the object to which Freud had originally alluded, now more fully articulated by Klein (ibid), enabled a more comprehensive understanding of the challenges of the normal mourning process. Klein thus highlighted that in order to achieve the other major position of psychic development, the Depressive position (D), the necessarily split ego and object had to ultimately become integrated. This meant that the good and bad representations had to come together. Klein claimed that this was a painful psychic process as it entailed recognition that the loved and hated objects were one and the same. One consequence of this developmental stage (the depressive position) is the anxiety generated by the belief that one’s hatred (sadistic impulses) towards the loved object must have damaged it.

As with all loss, the death of a child or the loss of a pregnancy results not only the loss of an external attachment, but also its related internal object or psychic representation. It is of course only the internal object which can be restored. In melancholic grief the self becomes impoverished due to the self-reproach it experiences. In the couple relationship unwanted projections of the self, prone to the harsh reproaches of a primitive superego, obviously thus contribute to the disharmony with which the couple presents. That is, in the couple dyad, the “other” can have projected into them unwanted and unacknowledged aspects of the partner’s self, associated with the partner’s melancholic reactions to the loss. The couple may also carry un-metabolised intergenerational losses that impinge upon the couple’s capacity for mourning. As Sigourney Prize-winning couple psychoanalysts David Scharff and Jill Savege-Scharff (1991) have noted, the couple dyad provides a unique vehicle for the maintenance and at times amplification of such splitting and projection.

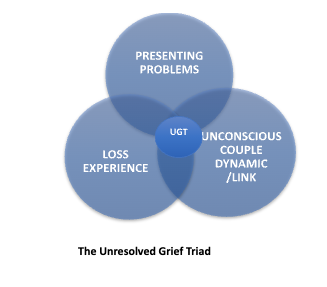

We have synthesised these psychoanalytic understandings to inform a short-term model for couples experiencing unresolved grief (Keogh & Gregory-Roberts, 2018). The sixteen-week intervention based on this model, which we provide free of charge through our psychoanalytic charity Penthos (penthos.org.au), conforms with contemporary evidence base about short-term interventions. It particular, for a short-term intervention to be successful, it must have a clear focus. In our case this means that the therapist keeps the issue of unresolved grief in the foreground. In order to facilitate this, we also make a psychodynamic formulation that is linked to our model and specifically its centrepiece, the Unresolved Grief Triad (UGT).

The Short-Term Model

Our short-term model consists of three main phases:

An assessment phase during which a specific psychodynamic formulation known as an Unresolved Grief Triad (UGT) is made and where aspects of this formulation are explicitly shared with the couple as part of an agreed upon therapeutic plan to work on their unresolved grief.

A working through phase (eight weeks) where the formulation shared with the couple is brought in and applied to material they bring each week, for example arguments the couple may have.

An ending phase (four weeks) where the themes developed are used and applied to the loss of the therapy and the therapist. That is an experiencing of tolerating loss.

In the first phase (four sessions) of the therapy the therapist attempts to articulate the interplay between the couple’s presenting problems (especially conflict in the relationship) and how these are linked to the recent loss experience. In addition, the therapist attempts to determine what contribution earlier (including inter-generational) unmourned losses might be contributing to their difficulties, as well as discerning the level of unconscious couple collusion, to avoid psychic pain that might be present.

In the working through stage of therapy (which consists of eight sessions) the issues implicit in the psychodynamic formulation, represented in the couple’s unique UGT, are worked with in relation to material they bring from their everyday life. This might involve, for example, bringing a different layer of meaning to arguments that may open up intense feeling in the couple.

Consider, for example, a couple Lind and Damian who had lost their child in a tragic car accident which occurred when both of them had been briefly distracted from monitoring their four-year old’s play. The couple came to one of the sessions in the working through phase indicating that they had a huge argument following our last session which had touched on feelings of self-reproach that were hard to stay with. Two days later the very painful argument erupted. This focussed on a plant that Damian had guaranteed to look after, as it was not thriving. Linda discovered the plant had died and “exploded” as it was her favourite plant which had been given to her by her mother. She said that Damian knew that the plant was fragile and yet he had forgotten to water it. The argument had become very bitter. In the session Linda tearfully asked, “How can I live with someone who I cannot trust to protect things?” I cautiously made a comment about how the argument might have symbolically hooked into some very painful feelings about the loss of their child. In particular (and mindful of the persecutory superego operating between them), I said she wondered if they judged themselves to have failed to pay sufficient attention to their child and that could never be forgiven? Responding to this, Damian who became quite distressed and tearful. I then commented how much each of them was suffering and feeling responsible. After this Linda, looking at Damian in his distressed state, commented that she felt awful about yelling at him and could now see how distressed he has been. After some minutes she embraced Damian as they both began to sob. At this point I just acknowledge the terrible pain associated with their traumatic loss. It was thus a very transformative event in the therapy of this previously well-functioning couple.

Let us look now at a more detailed vignette to illustrate how the UGT in our short-term model is formulated and used with the couple and touch on the working through and ending phases of the treatment.

Michael and Fiona

Michael and Fiona were a couple aged in their early forties who were referred 12 months after the death of their 6-year-old only daughter Anna from head injuries sustained by a falling tree branch, while on a family camping expedition. As the anniversary of Anna’s death approached Fiona’s GP became concerned that she had withdrawn from social contacts and felt unable to return to her part time work as a primary school teacher. The prospect of teaching lively, healthy children felt intolerable, and Fiona felt inadequate as a teacher and a parent. Michael and Fiona subsequently ruminated over Anna’s death, preserving her room as it had been at the time of her death and visiting her grave weekly.

As with the couple in Frost’s poem, Michael found it very difficult to relate to Fiona following their daughter’s death and retreated into a preoccupation with his work. She reacted to him as if he didn't feel the loss like she did and resented him for this. Consequently, their previously enjoyable sexual relationship was now avoided. Despite this, neither of them connected the deterioration of their relationship directly to their traumatic loss.

In terms of the couple’s history, Fiona’s mother had died quickly following a diagnosis of pancreatic cancer when Fiona was 18 years old. This occurred not long after a broken engagement initiated by Fiona’s fiancé, who was jealous and critical of what he believed to be her enmeshed relationship with her parents and extended family. She subsequently met Michael, a somewhat introverted and studious young architect.

Michael was happy to be part of a large family group, particularly as he had come from a family where his father was often absent travelling for work, resulting in Michael overhearing angry recriminations between his parents late at night. He feared his father’s anger and criticism, which he believed his mother endured for the sake of Michael and his brother.

Following the assessment and the provisional formulation represented by their UGT, the couple’s presenting problems were linked by me to the painful loss of their daughter. I also noted to myself that their fears of sharing the intense feelings generated by her death seemed to challenge an unconscious defensive couple link which they had co-constructed to avoid other un-mourned losses. I also noted how they had regressed to a paranoid-schizoid level of functioning following the death of their daughter, resulting in each seeing the other as a persecutory object exacerbating their guilt and self-blame. One can see in this example, especially in such short-term analytic work, how important the analyst’s internal work of processing is and how essential it is to have the support of a trusted and secure peer group.

I shared with the couple that it seemed that the current loss resonated on some past losses for them and that it might be helpful for us to think about this together. The part of my formulation was accepted by them with some caution. While keeping grief at the forefront of their therapy in real time, I subsequently used the material from their everyday lives to help understand and facilitate them processing their grief as a couple. An example of this was in the eighth session when they came to the session reporting that they had an argument about the fact that a new little puppy they had acquired had escaped outside narrowly missing being hit by a car, given they live on a busy road. Fiona said that this happened whilst she was out, and she felt that Michael had not been vigilant enough about making sure that the front door was locked. (The puppy was allowed to go out to the safety of the back garden.) The couple was surprised at the intensity of the argument. Michael said that Fiona just “lost it”. Through a series of iterative interpretations, I pointed to how in the argument that the central issue that felt so upsetting was that someone had to be blamed for not being sufficiently vigilant. After feeling I had engaged them by introducing some mentalising of their strong feelings, I made a made a further link to the loss of Anna. I noted that there seemed to be a link to a belief that they were struggling with a belief that not being vigilant at every moment meant they were responsible for her death. This resulted in a notable feeling of relief in the couple. Following this and further work on their respective feelings of guilt, they reported arguing less and that they had been able to talk about plans for a memorial for their daughter.

By this stage the couple were very engaged with me, yet I was aware, as one always is in short-term intervention, that we were approaching the ending phase of the brief intervention. I experienced countertransference feelings of pressure about the time left and concern about their ability to manage. Fiona became quite tearful talking about the impending end of our work. Michael said that in this regard he was worried how Fiona would cope. I said perhaps he was also worried about himself. At the same time, I noted that as a couple they had been able to face some excruciatingly painful feelings together which had opened up, in the way Shahid will describe, feelings of hope about the future. In one session they had collapsed into what at the time seemed an unbearable and oceanic feeling of misery and despair that we needed to endure together. I noted we had done this and now how as a couple they could continue to recover together.

Once again, this couple exemplified the often extreme and harrowing pain of mourning the loss of a child and the associated powerful push away from depressive position functioning, even in previous well-functioning couples. The couples therapist, in encountering the sometimes powerful forces of projective identification and strong countertransference feelings, has much to manage in their internal work, with the therapist feeling as Rilke describes at times:

‘It’s possible I am pushing through solid rock

in flintlike layers, as the ore lies, alone;

I am such a long way in I see no way through,

and no space: everything is close to my face,

and everything close to my face is stone.

I don’t have much knowledge yet in grief

so this massive darkness makes me small.’

Conclusion

In this paper I have attempted to show the enduring value of psychoanalytic understanding about unresolved loss in managing this clinical situation. I have also attempted to show how these understandings distilled into a short-term intervention can be surprisingly successful when applied to couples presenting with distress and risk to their relationship emanating from unresolved loss.

From a psychodynamic perspective I have argued that a predisposition to a melancholic reaction to loss is intrinsically linked to the extent to which a human being has developed a sense of himself as being psychologically separate from others. In this regard I note that much of the recent research concerning complicated grief has indirectly vindicated Freud’s (1917) original ideas, expressed in that which many consider to be a psychoanalytic gem, that is, his paper Mourning and Melancholia.

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements

In presenting this work I wish to acknowledge not only Cynthia Gregory-Roberts (Co-Editor with me of Psychanalytic Approaches to Loss: Mourning and Melancholia in Couples), but also Penthos’ experienced and dedicated couple therapists Ofelia Brodsky, Kaye Nelson, Allan Tegg, Maria Kourt, John Kearney, Judith Pickering, Rebecca Codrington and Chloe Khoury who, though their work and peer group involvement, are deepening the understanding of unresolved grief in couples.

References

American Psychiatric Association. (2022). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed., text rev.). https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.books.9780890425787

Freud, S. (1917). Mourning and Melancholia. S.E., 14: 239-258.

Frost, R. (2013). The collected poems. Vintage Classics.

Klein, M. (1945). Love, Guilt and Reparation. London: The Hogarth Press.

Keogh, T., & Gregory Roberts, C. (2018). Psychoanalytic Approaches to Loss: Mourning, Melancholia and Couples. Routledge. London

Kubler-Ross, E. (1970). On Death and Dying. London: Tavistock.

Neimeyer, R. A. (2002). Traumatic loss and the reconstruction of meaning. Journal of

Palliative Medicine, 5(6): 935-942.

Neimeyer, R. A. (2008). Prolonged grief disorder. In: C. Bryant and D. Peck (Eds.)

Encyclopedia of death and the human experience. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Parkes, C. (1972). Bereavement: Studies of grief in adult life. London: Tavistock.

Prigerson H, Frank E, Kasl S, Reynolds CF, Anderson B, Zubenko G. S., et al. (1995). Complicated grief and bereavement-related depression as distinct disorders: Preliminary empirical validation in elderly bereaved spouses. American Journal of Psychiatry, 152: 22–30.

Prigerson, H.G., Shear, M.K., Jacobs, S.C., Reynolds, C. F., III, Maciejewski, P.K., Davidson, J.R.T., Rosenheck, R., et al. (1999). Consensus criteria for traumatic grief: A preliminary empirical test. British Journal of Psychiatry, 174: 67–73

Rilke, R. M. (1981) “Pushing Through” in Selected Poems of Rainer Maria Rilke, Translated and Edited by Robert Bly New York: Harper and Row.

Shear, M. K., & Shair, H. (2005). Attachment, loss and complicated grief.

Developmental Psychobiology. 47: 253–267.

Stroebe, M., Schut, H., & Stroebe, W. (2005). Attachment in coping with bereavement: A theoretical integration. Review of General Psychology, 9(1): 48-66.